How Do We Build a Global Hydrogen Economy?

The hydrogen industry is small, centralized, and carbon intensive. What needs to happen in order for hydrogen to fulfil its potential as a versatile, carbon-neutral fuel?

Hydrogen is considered a critical element of the energy transition. It has the potential for integration across the entire energy system: as feedstock for hard-to-abate industries; balancing renewable-heavy grids; complementing the future carbon capture, storage, and utilization (CCUS) economy; and supporting a new business model for fossil fuel exporters.

The hydrogen economy today

There is great political excitement around hydrogen: Japan has announced its intention to become a 'hydrogen-based society', the UK aims to lay the foundations of its hydrogen economy by 2030, and the UAE is targeting 25 percent of the global market by 2030. According to engineering and consultancy firm Black & Veatch, demand for hydrogen is 'poised to skyrocket'.

"Despite decades of buzz about hydrogen, the market is still really in its infancy," says IEF analyst Allyson Cutright. It accounts for just one percent of the energy mix, is highly centralized, and is associated with 915 million tons of CO2 emissions annually. Establishing a hydrogen economy that meets our climate needs calls for cross-sector collaboration and policy support to reduce cost and risk for investors, incentivize low-carbon hydrogen production and accelerate technology and infrastructure development.

Missing infrastructure

At present, most hydrogen is produced and consumed on site, usually refineries. There is serious need for construction of hydrogen infrastructure, particularly for storage and transport. This can be largely based around existing energy and transport infrastructure, such as ports and natural gas pipelines. For instance, a project is underway in the UK to deliver blended hydrogen and natural gas through the existing public gas network. The company behind the initiative says that adapting existing infrastructure in this way across the UK could save around 6 million metric tons of CO2 every year – the equivalent of taking 2.5 million cars off the road. Meanwhile, a $9bn hydrogen project in Namibia aims to make use of the rich renewable resources nearby.

There remains difficulty, however, in attracting investment in expensive, unproven projects due to uncertainty regarding both supply and demand.

"The creation of the hydrogen market isn't occurring organically in the free market; it is driven by climate concerns," explains Cutright. "It will need further policy support to de-risk on both the supply and demand-side." She suggests policymakers could mitigate risk for investors through long-term carbon pricing, contracts for difference, and by ensuring their hydrogen roadmaps have clear goals, such as quantitative supply and demand targets.

Closing the green gap

Today, green hydrogen – made using renewable energy - is two to three times more expensive than blue hydrogen – produced from natural gas in combination with CCUS – and up to 10 times more than unabated fossil fuel-based hydrogen. While blue hydrogen has potential to meet demand while green hydrogen becomes more affordable, most operational hydrogen plants do not employ CCUS. For hydrogen to play its much-vaunted role in decarbonization, governments must incentivize low-carbon hydrogen production.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development has ranked a range of mechanisms to incentivize hydrogen products according to their capacity to help meet the 1.5°C scenario of the Paris Agreement. At Cop26 in Glasgow, it announced pledges from 28 companies across multiple sectors to address uncertainty in both supply and demand for low-carbon hydrogen. It estimates these pledges could help avoid more than 200 million tons of CO2 emissions annually.

It would be beneficial to establish an internationally recognized system of certification and standardization for carbon intensity of hydrogen, in addition to its safety, quality, and origin. For instance, a G20 Insights report suggests setting standards for maximum CO2 emissions for green and blue hydrogen, with sub-categories relating to carbon intensity. The standards-setting process would be helped by collating data on every aspect of the hydrogen economy, such as via the Joint Organisation Data Initiative.

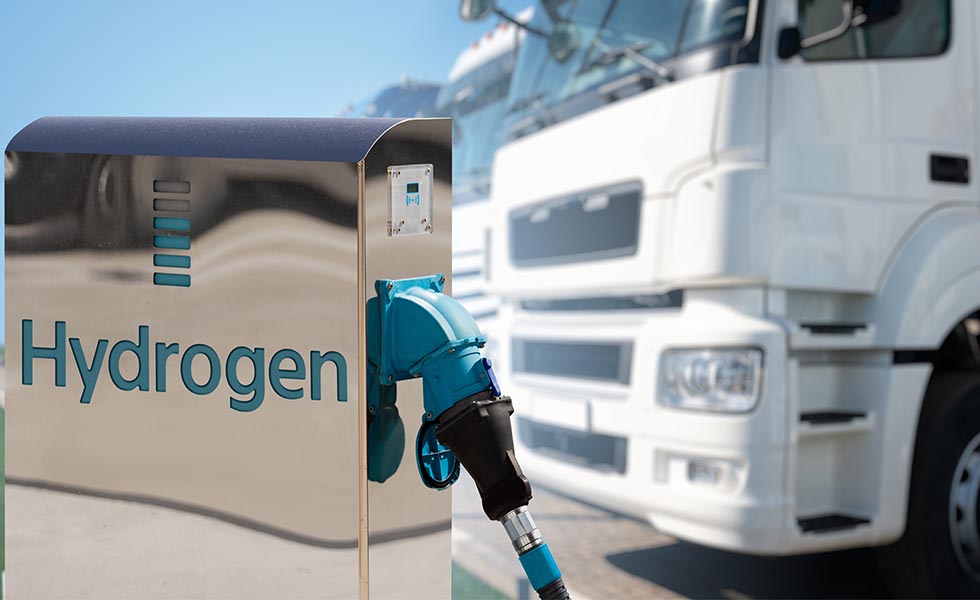

Everyone in

The acceleration of the hydrogen economy calls for a coordinated response between sectors, countries, and international bodies. For instance, as a major energy importer, Germany plans to work with international partners to reach its target of 6GW of green hydrogen capacity by 2030 and has set aside funds to do so. Energy companies will work with partners across sectors, from transport to heavy industry; BP and Daimler recently announced a joint project aiming to accelerate a UK-based hydrogen network to support fuel cell-powered trucking.

A stable, green hydrogen economy is critical to the ambitions of many companies, sectors, and governments. Everyone must be involved to ensure it grows quickly, and in the right direction, to fulfil its promise.